A Quick Guide to the New U.S. Trade Regime

This is a major structural shift to the global economy, here I review the basics.

The United States launched a bold trade policy shift under a new executive order issued in April 2025. In this post, we will cover:

The Basics

What are tariffs, and who ends up paying them?

Do tariffs raise prices? (See attached document for detailed analysis.)

The New U.S. Trade Regime

What’s the motivation behind this policy?

How is it being implemented? (See attached document for detailed analysis)

What are the key legal considerations?

Background

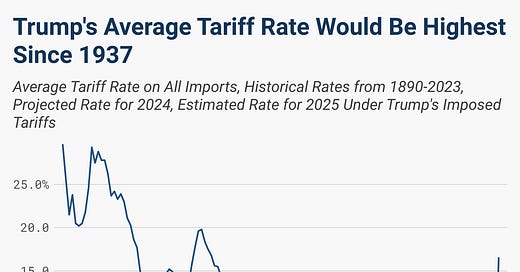

The early months of the new U.S. administration have been marked by an intense use of executive authority to reshape American trade policy and the global trade order. I see this as a defining moment from the perspective of the international trade system with possible implications in terms of the functioning of the international monetary system as well. At the center of this effort is the use of tariffs.

For those who have followed the speeches, interviews, and publications from members of the current administration, the final outcome is not that surprising. Personally, I found the broad-based implementation unexpected (i.e., I would have imagined a more targeted approach). In any case, I would classify the evolution of this trade strategy into two key steps.

a) Opioid Tariffs (Canada, Mexico, China)

The first wave of tariffs came in the context of executive orders addressing the fentanyl and synthetic opioid crisis. These measures were initially justified on national security and public health grounds, particularly with respect to precursors sourced from China and trafficking through Mexico and Canada. For readers interested in the deeper policy context, the Select Committee Report of April 2024 summarizes the issue.

These measures have been subject to back-and-forth action. They have been announced, postponed, and then finally implemented at the beginning of March with a tariff of 25% on all goods imported from Canada and Mexico that do not satisfy U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) rules of origins, with an exception of a tariff of 10% on the automotive industry.

“In order to minimize disruption to the United States automotive industry and automotive workers, it is appropriate to adjust the tariffs imposed on articles of Canada (and Mexico my add on) in Executive Order 14193 of February 1, 2025 (Imposing Duties to Address the Flow of Illicit Drugs Across Our Northern Border).

For China, tariffs based on the opiods crisis have been raised to 20% as of March 2025.

b) Reciprocal Tariffs (“Liberation Day” Tariffs)

The second—and more consequential—wave came with the introduction of reciprocal tariffs. Announced on what was symbolically referred to as “Liberation Day,” these tariffs were aimed at correcting longstanding imbalances in trade relationships. The core idea was to move away from unilateral trade liberalization toward a model based on reciprocal treatment—what the administration frames as “fair trade.”

It’s worth noting up front that all of these trade measures have been taken under the authorities provided by the National Emergencies Act (NEA) and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). These acts give the president broad discretion to impose tariffs and other restrictions in response to national or international threats.

But before looking into the actual policy actions, let’s review the background concept.

What Are Tariffs and Who Pays Them

Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported goods. In general, countries impose tariffs and other import duties. In the case of the United States, these include customs duties, excise taxes, merchandise processing fees (MPF), and harbor maintenance fees (HMF).

Pre-New Trade Order, these charges are applied based on the type and value of goods imported by the United States.

U.S. importers, not foreign exporters, pay tariffs.

Effectively, who bears the cost depends on supply chain dynamics: importers may pass the cost to consumers, absorb it, negotiate price reductions with suppliers, or find new sourcing altogether.

Most goods valued under 800 dollars are exempt from tariffs under the de minimis rule. However, as of February 2025, this no longer applies to goods from China or Hong Kong, regardless of shipping origin. All such imports now require formal customs clearance and are subject to full duties.

How do Tariffs Affect Prices?

In the attached document, I provide a more detailed and analytical account of how tariffs affect prices. Here, I summarize the main points. First, I introduce the concept of pass-through, i.e., the share of a tariff that ends up being reflected in the domestic price. If a 20% tariff raises prices by 20%, that's full pass-through. If the price increase is smaller than the tariff rate, the effect is partial.

The effect of tariffs on prices might depend on several factors:

General equilibrium effects: There might be currency moves or wage feedbacks that can also offset or amplify the initial effect of tariffs.

Currency invoicing: if imported goods and services are priced in U.S. dollars, then the exchange rate does not matter, while if they are priced in foreign currency, a stronger dollar can limit their impact.

Another important aspect is the time horizon: for example, when we consider tariffs on intermediate input, in the short run, a domestic firm might not be able to adjust by substituting input because supply chains are sticky,

For direct imports, pricing is straightforward:

Price = (1 + tariff) × exchange rate × foreign priceWhen tariffs hit inputs (like components or raw materials), the outcome depends on production structure:

What share of costs comes from the input?

How easy is it to swap in an alternative?

With high substitution (elasticity > 1), firms shift away from taxed imports. Pass-through is low. With low substitution (elasticity < 1), firms are stuck. The taxed input makes up more of their costs. Pass-through is high.

In the current situation, another aspect is relevant: the new U.S. tariffs are unusually broad and steep, so as substitution is low in the short run, their pass-through increases with the increase of the tariff.

The New U.S. Trade Order

What Did Trump Do in April 2025?

On April 2, 2025, President Trump issued a sweeping executive order declaring a national emergency based on persistent U.S. trade deficits and foreign trade practices. The order includes:

A 10 percent across-the-board tariff on nearly all imported goods, effective April 5, 2025

Additional country-specific tariffs, up to 46 percent, based on trade imbalances and reciprocity criteria, effective April 9

The passage in the executive order that provides the details of the policy action reads as follows:

The additional ad valorem duty on all imports from all trading partners shall start at 10 percent and shortly thereafter, the additional ad valorem duty shall increase for trading partners enumerated in Annex I to this order at the rates set forth in Annex I to this order. These additional ad valorem duties shall apply until such time as I determine that the underlying conditions described above are satisfied, resolved, or mitigated.

As a side comment, note that the last part of this paragraph suggests the potential scope for negotiations or adjustments conditional on the mitigation of underlying conditions that are behind the policy actions (see below).

Moreover these duties apply to the non-US content of foreign imported items. This means that if a product contains both U.S. and foreign parts, the tariff is not applied to the U.S. portion of the product. (The idea is to protect domestic value-added and avoid taxing U.S. producers who contribute to global supply chains). This exception only kicks in if the U.S. content makes up at least 20% of the total value of the product. If the U.S. content is less than 20%, the full value of the good may be subject to tariffs.“U.S. content” refers to parts that are made entirely in the U.S., or substantially transformed in the U.S. (meaning foreign inputs are significantly changed through processing or manufacturing).

These measures apply regardless of World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations or free trade agreements such as the USMCA.

What’s the Rationale Behind This Move

The rationale for this action is explicitly addressed in the executive order:

“Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries. Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits are caused in substantial part by a lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships. Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries. Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits are caused in substantial part by a lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships.”

The administration links trade imbalances to a range of economic and national security concerns. These include non-reciprocal tariffs and non-tariff barriers that block U.S. exports, foreign policies that suppress domestic wages and demand, and persistent trade deficits that have hollowed out the U.S. manufacturing base.

In addition, vulnerabilities in global supply chains are portrayed as threats to national security and military readiness. The policy’s central principle is reciprocity: U.S. tariffs should mirror the barriers faced by American exporters abroad. The foreign trade barriers document also provides background information behind this perspective.

How Are These Tariffs Calculated

The executive order adopts a reciprocal tariff strategy aimed at rebalancing bilateral trade by reducing U.S. imports from specific countries until they match U.S. exports to those countries. The underlying method is rooted in a partial equilibrium framework that quantifies how much imports must fall to close the trade gap and then computes the tariff increase needed to achieve that fall, assuming no currency movement or retaliation.

To reduce imports from a country to match U.S. exports, the tariff increase must satisfy:

Change in tariff = (exports – imports) / (elasticity × pass-through × imports)

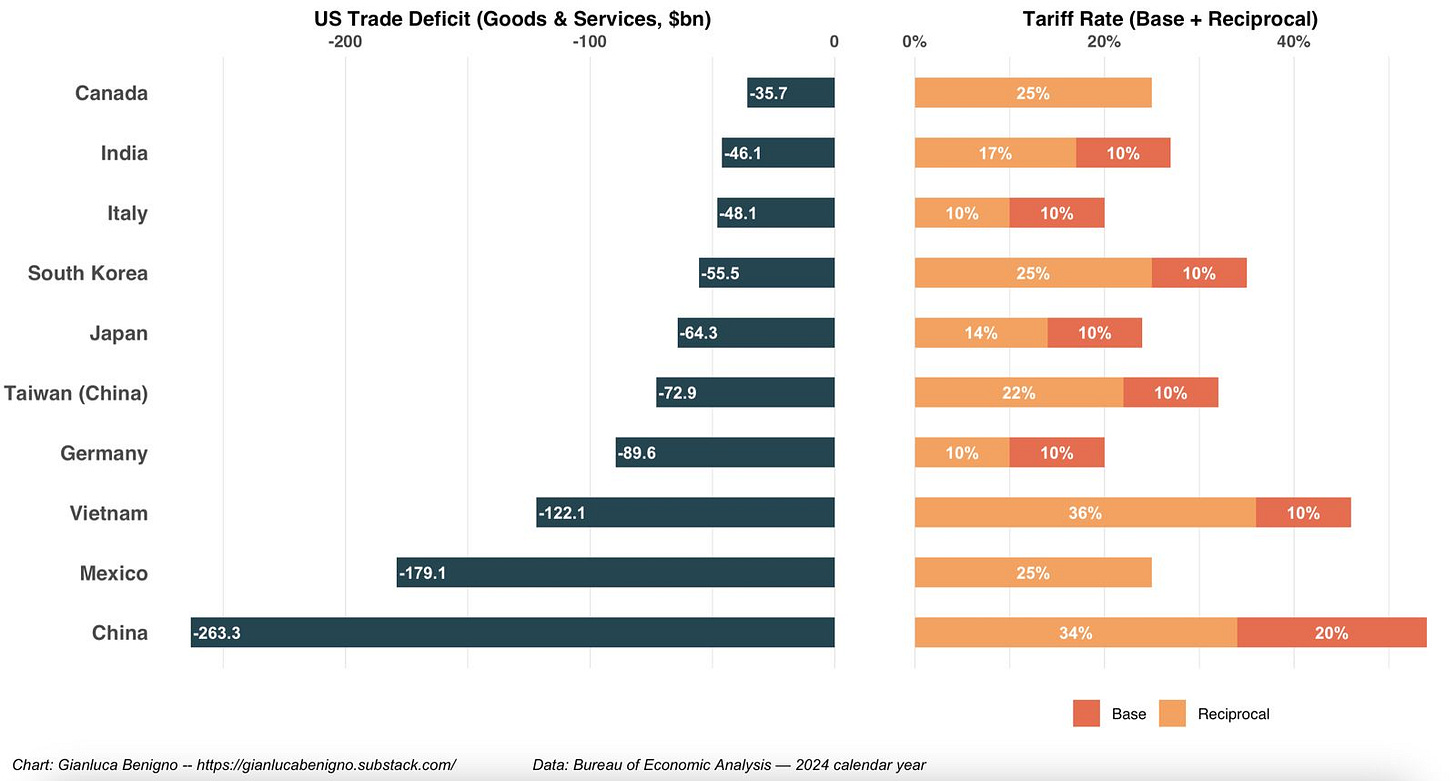

This formula implies higher tariffs on countries with large trade deficits and low import elasticity, such as China and Vietnam.

The following graph provides a visual in terms of the U.S. total import of goods in billions of dollars and the corresponding tariffs.

The model abstracts from retaliation, exchange rate adjustments, or broader macroeconomic dynamics, making it a short-run, demand-side framework focused purely on import compression as a rebalancing tool.

The Legal Foundation

Trump’s order invokes broad executive powers under the following statutes:

International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)

National Emergencies Act (NEA)

Section 604 of the Trade Act of 1974

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which allows presidential delegation of trade authority

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974

Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930

Together, these provisions allow the president to declare a national economic emergency and impose tariffs unilaterally, bypassing the need for Congressional approval.

The executive order raises serious concerns regarding World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Under GATT (GATT stands for the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. It was created in 1947 as an international treaty to promote trade by reducing tariffs, quotas, and other trade barriers among member countries.):

Article I prohibits discriminatory tariffs, enforcing the Most-Favored Nation (MFN) principle

Article II commits members to bound tariff ceilings

Article XIX permits safeguard measures, but only under strict procedural requirements

The administration is instead invoking Article XXI, the national security exception. However, recent WTO rulings—particularly concerning past U.S. steel tariffs—have narrowed the acceptable use of this clause. Legal challenges and retaliatory measures are likely. China has already signaled its intent to challenge the U.S. action through the WTO dispute settlement process and retaliate by announcing a 34% tariff on U.S. imports.