Background Note on Trade and Trade Imbalances

I did this notes for one of my courses as a background to review the classical concepts in terms of imbalances from trade and international finance perspective.

Introduction

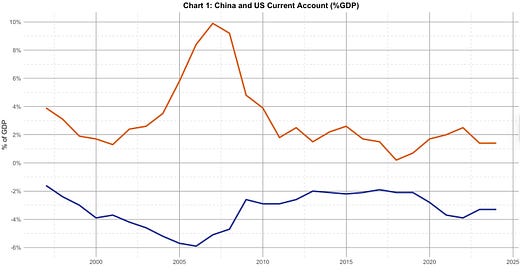

For decades, the United States and China have been on opposite sides of global trade imbalances. Since the 1990s, the U.S. economy has been characterized by persistent current account deficits, while on the other hand, China’s economy has run current account surpluses for over 25 years (see Chart 1). While these imbalances have narrowed somewhat since their peak around the 2008 global financial crisis, they remain a defining feature of the international trade and monetary system.

As policymakers debate the role of tariffs and trade restrictions, it’s useful to review the economic logic behind trade and current account imbalances. Why do trade imbalances persist? Are they a symptom of unfair trade practices, or do they arise naturally from economic forces? And most importantly, do tariffs help correct these imbalances—or do they simply shift them around?

In this blog, I take a step back from these key questions and outline, in a simplified roadmap, how economists think about trade and current account imbalances.

I will start by distinguishing between the static perspective of classic trade theory—which explains why countries trade in the first place—and the intertemporal approach, which examines how trade imbalances evolve over time. These two perspectives are not necessarily distinct, and indeed, some important recent studies discuss their integration (see, for example, Ghironi and Melitz (2007) “Trade Flow Dynamics with Heterogeneous Firms”).

Key takeways

Trade imbalances are not temporary distortions—they are persistent features of the global economy. The U.S. has run current account deficits for decades, while China has maintained sustained surpluses. The key question is: Why haven’t these imbalances corrected themselves?

Classical trade theory assumes balanced trade, but reality tells a different story. Traditional models explain why countries trade, but they struggle to account for long-term deficits and surpluses.

The global monetary system plays a crucial role. The U.S. provides the world with safe and liquid assets (such as U.S. Treasuries), which surplus economies’ demand. This structural feature sustains, rather than eliminates, imbalances.

A richer economic framework is needed to understand these dynamics. Explaining persistent imbalances requires integrating trade theory, financial flows, and the structure of the international monetary system—not just focusing on trade alone.

The Static Perspective of Trade: Trade Theory and the Gains from Trade

Let me start with what I would refer to as a static perspective of trade.

Trade theory typically assumes a world where trade balances instantaneously, meaning that relative prices adjust such that the value of exports equals the value of imports. Different theories offer different rationales for why trade occurs:

(a) Comparative Advantage (Ricardian Model)

The Ricardian model explains trade through differences in relative productivity across countries, emphasizing comparative advantage. Countries export goods for which they have a lower opportunity cost to produce and import those for which they have a higher one. A key insight of this model is that specialization should be based on comparative, not absolute, advantage—meaning a country benefits from focusing on goods where its opportunity cost is lower, even if it is more efficient in producing both. An essential feature of this mechanism is that relative prices adjust endogenously to ensure balanced trade.

(b) Factor Proportions Theory (Heckscher-Ohlin Model)

The Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model explains trade through differences in factor endowments. Countries export goods that intensively use their abundant factor and import goods that rely on their scarce factor. For example, a capital-rich country exports capital-intensive goods, while a labour-rich country exports labour-intensive goods. As in the Ricardian model, relative factor prices adjust endogenously to clear markets and ensure balanced trade.

(c) New Trade Theory: Scale Economies, Product Differentiation, and the Pattern of Trade (Krugman, 1980)

Unlike previous models, Paul Krugman’s seminal 1980 article “Scale Economies, Product Differentiation, and the Pattern of Trade” introduces intra-industry trade, laying the foundations of the New Trade Theory. New Trade Theory explains why trade occurs even between similar countries by incorporating increasing returns to scale and consumers’ preference for variety. According to the theory, countries specialize in different varieties of similar goods (e.g., German vs. Japanese cars), such that the rationale for trade arises without appealing to the Ricardian notion of comparative advantage or the factor proportions argument of Heckscher and Ohlin, but rather purely from economies of scale and preference for variety.

Let’s examine this model through the case of two countries that specialize in automobile production: Germany and Japan. Traditional trade models, such as Ricardian or Heckscher-Ohlin, predict that trade arises from differences in productivity or factor endowments. However, Germany and Japan share similar levels of technology, skilled labor, and capital. Why, then, do they engage in extensive trade in automobiles?

Krugman’s model provides an answer by introducing two key concepts: economies of scale and consumers’ preference for variety. In each country, car manufacturers produce different brands—BMW and Mercedes in Germany, Toyota and Honda in Japan. If these countries did not trade, German consumers would have access only to German cars and Japanese consumers only to Japanese cars. Since the domestic market is limited, car manufacturers would produce at a smaller scale, leading to higher production costs and prices.

Now, consider what happens when trade opens between Germany and Japan. German automakers no longer sell only to German consumers – they can now export to Japan, significantly expanding their customer base. The same happens for Japanese automakers, which now sell to German consumers. With a larger market, each car manufacturer produces at a greater scale, spreading fixed costs over a larger number of vehicles. This reduces the average cost per car, making them more affordable for consumers.

At the same time, consumers in both countries benefit from increased variety. A German customer who previously had to choose between BMW and Mercedes can now also buy a Toyota or Honda. Likewise, a Japanese customer who once had only domestic car brands available can now purchase a German-made vehicle. Trade, therefore, is not driven by fundamental differences between the countries but by the desire for variety and the efficiency gains from larger-scale production.

In the original Krugman (1980) model, trade is always balanced. The model assumes a static framework in which each country’s total exports equal total imports, meaning that there are no trade surpluses or deficits.

(d) “New” New Trade Theory: Trade with Heterogeneous Firms (Melitz, 2003)

In 2003, Marc Melitz’s highly influential article titled “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity” paved the way for the most modern version of New Trade Theory, denominated “New” New Trade Theory. The Melitz (2003) model builds on Krugman’s framework but introduces an important new element: firm heterogeneity—the idea that not all firms are equally productive.

Imagine an industry where many firms produce similar goods, but some are much more efficient than others. In a closed economy, even low-productivity firms can survive because they face no external competition. But once trade opens, a sorting process begins.

Highly productive firms benefit the most because they can scale up production and sell to international markets. They overcome trade costs and expand their reach, making higher profits. Medium-productivity firms may survive but only sell domestically, as they are not productive enough to profitably cover the extra costs of exporting. Low-productivity firms, however, struggle to compete with imported goods sold by foreign exporters and may be forced to exit the market entirely.

As a result, trade leads to a reallocation of resources within the industry. The most productive firms grow and gain market share, while the least productive ones disappear. This process raises overall industry productivity and improves efficiency. Moreover, the Melitz model shows that trade creates winners and losers—exporting firms gain, but weaker domestic firms may shut down.

This has implications for the trade balance as well. Since only the most productive firms export, trade openness can lead to a trade surplus in industries where a country has a strong concentration of competitive firms. Meanwhile, industries with fewer highly productive firms may see increased imports and a worsening trade balance. The Melitz model helps explain why, within the same country and industry, some firms thrive in global markets while others struggle—or disappear altogether.

In the original Melitz (2003) model, trade is always balanced. This is because the model assumes a static equilibrium framework where each country’s trade flows adjust through relative price movements to ensure that exports equal imports. If a country’s exports become too large relative to imports, prices and wages will adjust to bring trade back into balance. For example, if a country exports more than it imports, its wages rise, making its goods relatively more expensive, thereby reducing exports and increasing imports.

(e) The Eaton-Kortum Model (A Ricardian Trade Model with Geographic Frictions)

The Eaton-Kortum model, developed by Jonathan Eaton and Samuel Kortum in their 2004 article “Technology, Geography, and Trade” builds on the idea of comparative advantage but introduces two important features: differences in technology across countries and the role of geographic trade costs. Instead of assuming that each country specializes in a single good, the model views trade as a competition where countries bid to supply goods in global markets. The most productive and low-cost supplier wins, but distance and trade costs influence the final outcome. Countries do not necessarily import from the absolute cheapest producer but rather from the cheapest supplier after accounting for transportation and trade barriers. This explains why geography plays a crucial role in shaping trade flows alongside productivity differences.

The Eaton-Kortum model explains how countries don’t necessarily trade only with the most efficient producer but instead choose trade partners based on a mix of costs, productivity, and distance.

This also helps explain why geography matters in trade: Even if a distant country has the best technology, high transportation costs might prevent it from becoming the main supplier. This is why, for example, the U.S. trades heavily with Canada and Mexico, while European countries primarily trade within the EU.

In the original Eaton-Kortum (2002) model, trade is always balanced at the country level. This means that each country’s total value of exports equals its total value of imports. The model does not allow for trade deficits or surpluses because it is a static model that does not include intertemporal borrowing or lending.

In short, we have seen how in the models reviewed above, different motives underly the gains from trade, but in all of them, the trade balance is imposed to be equal to zero, and equilibrium prices adjust accordingly.

The Intertemporal Perspective: Trade Imbalances and the Role of the Current Account

The static models above assume that trade is always balanced, but in reality, trade deficits and surpluses could arise due to intertemporal considerations. This perspective introduces the current account as a buffer for economic shocks.

The intertemporal approach to the current account emerged in the mid-1970s as economists sought to understand how economies respond over time to various shocks, including significant events like the oil price hikes of that era. This framework integrates principles from consumption theory, emphasizing how forward-looking decisions on saving and investment influence a nation's current account balance.

What are the foundations of the Intertemporal Approach?

Traditional analyses often viewed the current account—the difference between a country's savings and its investments—as a static indicator. In contrast, the intertemporal approach considers it a dynamic outcome of decisions made by agents (households, firms, governments) aiming to optimize their utility or profits over time. This perspective builds upon the life-cycle and permanent-income hypotheses in consumption theory, which propose that individuals base their consumption not just on current income but on anticipated future income.

Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff's Handbook of International Economics Chapter 34, "The Intertemporal Approach to the Current Account", offers a comprehensive survey of this framework.

A central concern of the intertemporal approach is distinguishing between temporary and permanent economic shocks:

Temporary shocks: short-term disturbances, such as a sudden but brief increase in oil prices. Economies might respond by borrowing internationally to smooth consumption, leading to a current account deficit that is expected to reverse once the shock dissipates.

Permanent shocks: Long-lasting changes, like a sustained rise in oil prices, necessitate more profound adjustments. Economies may need to reduce consumption and increase savings to adapt to the new reality, potentially resulting in a current account surplus as they build reserves for future challenges.

The nature of the shock—whether perceived as temporary or permanent—significantly influences the response and the trajectory of the current account balance.

An Example: Oil Price Shocks of the 1970s

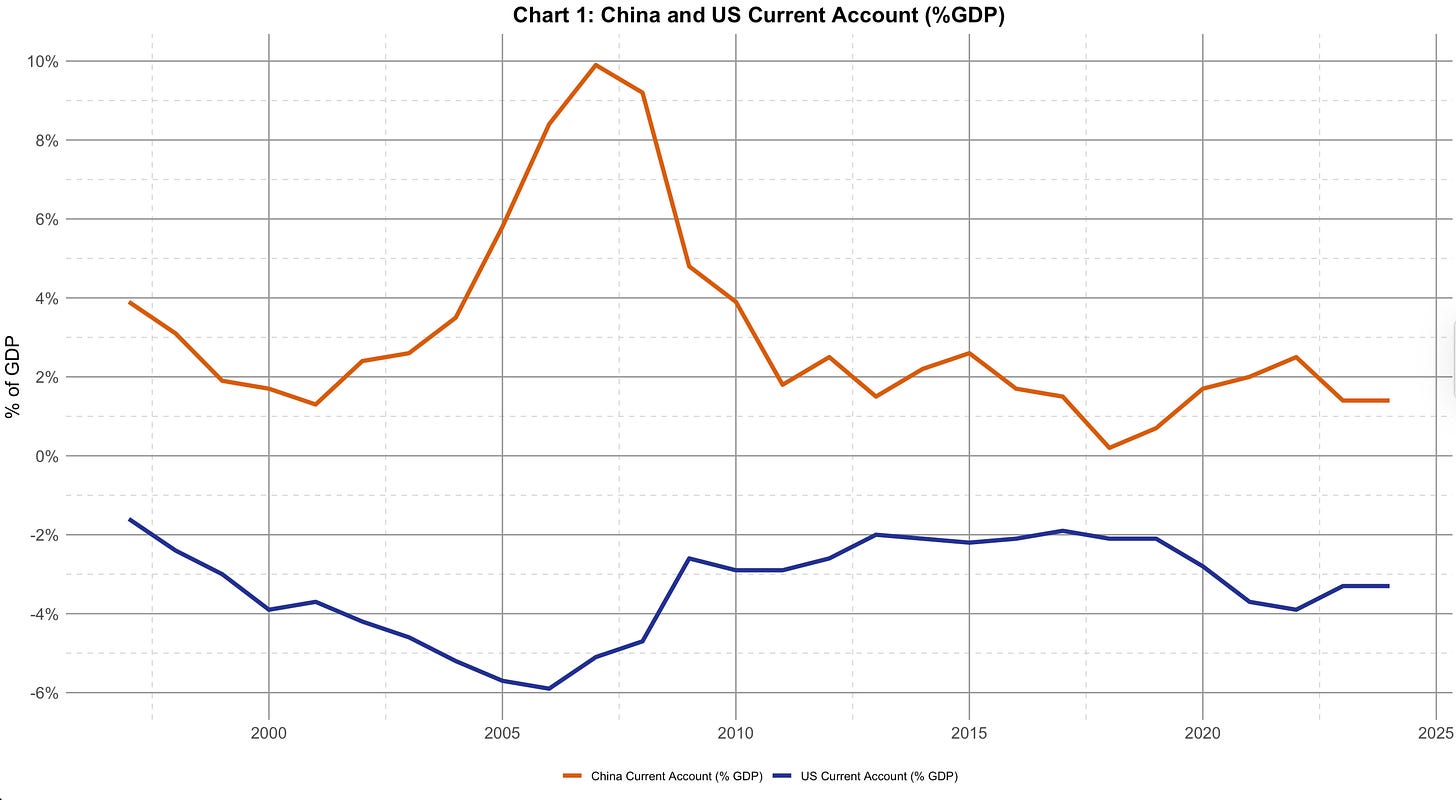

The oil crises of the 1970s serve as pivotal examples:

1973 Oil Crisis: triggered by geopolitical tensions, notably the Yom Kippur War, oil prices quadrupled. This supply shock led to stagflation—a combination of stagnant economic growth and high inflation—in many oil-importing nations.

1979 Energy Crisis: The Iranian Revolution caused another spike in oil prices, exacerbating economic challenges for oil-dependent countries.

These shocks prompted significant current account imbalances. Oil-importing countries faced deficits as they borrowed to finance higher oil import bills, while oil-exporting nations accumulated surpluses (see Chart 2).

Let’s now look at it more carefully from an accounting perspective.

The current account is the sum of the trade balance and net income from abroad:

Current Account = Trade Balance + Net Income on Foreign Assets

The trade balance consists of the difference between exports and imports, while the net income on foreign assets is the net return on the net external position.

More formally:

where CA stands for the current account, TB is the trade balance, B is the net foreign asset (stock variable), and r is the net rate of return on the net foreign asset position.

B > 0 denotes a credit position, and B < 0 denotes a debt position.

When a country runs a current account surplus in a given period t, CA > 0, it improves its net position so that in the next period

Viceversa, when a country runs a current account deficit in a given period t, CA < 0, it worsens its net position so that in the next period

When does a country run a current account surplus/deficit?

In general, temporary shocks (e.g., recessions, investment booms, demographic changes) cause temporary imbalances in the current account. When the current account is in deficit, the country is effectively consuming more than what it is producing. In this case, the country borrows from the rest of the world and accumulates external debt. Vice versa, when the country runs a surplus, it is lending to the rest of the world and is accumulating external credit.

Over time, these imbalances should unwind as all debt must eventually be settled: Countries that run deficits should repay their debt, and surplus countries should reduce their asset accumulation.

In equilibrium, a country is subject to a constraint that confines its consumption possibilities to what it produces over time. Formally, the intertemporal budget constraint must hold:

This means that persistent deficits require future surpluses.

In an ideal long-run equilibrium with no shocks, we would usually have

Where CA denotes the current account in the long run.

Does this imply that the trade balance in the long run is also equal to zero, i.e. TB=0?

Not necessarily. In the long run, a country may run a trade deficit if the income from its positive net foreign asset position offsets its trade imbalance:

So, if TB < 0 (the country runs a long-run deficit), then B > 0 (the country has a positive net foreign asset position vis-à-vis the rest of the world). Hence, under the lens of the intertemporal perspective, we have introduced financial integration considerations in thinking about trade (more specifically, intertemporal trade).

To summarize this short and informal review of the literature: from both the static and intertemporal perspective in their simplest form, trade and trade imbalances are the manifestation of the efficient response of the economy to economic integration and shocks. Moreover, in this integrated equilibrium, both the trade balance (as in standard trade models) and the current account (as in the intertemporal approach) would be balanced in the long run.

The Current Imbalances

But let’s now focus on the current situation and in particular on the U.S.- China Imbalances.

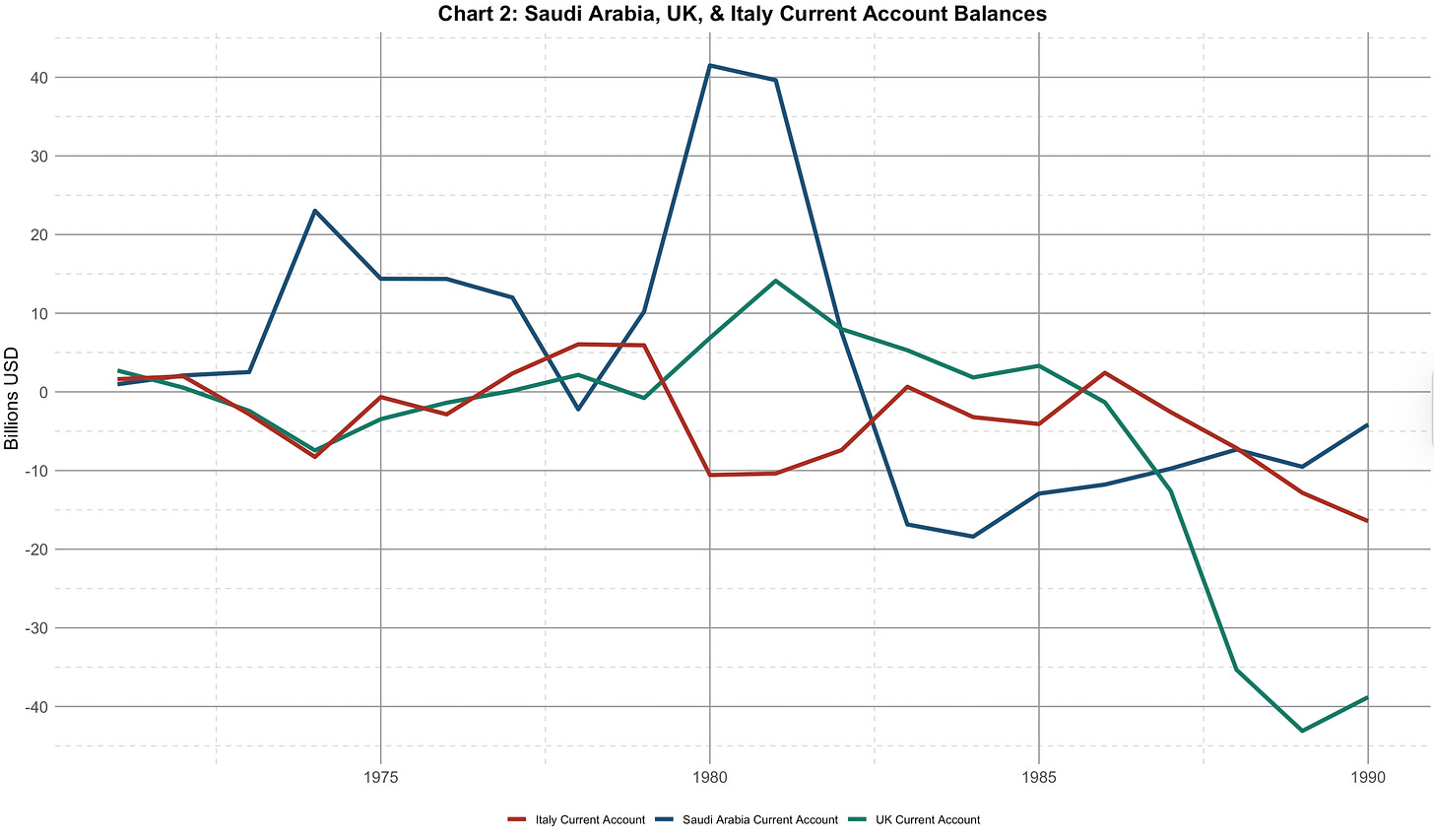

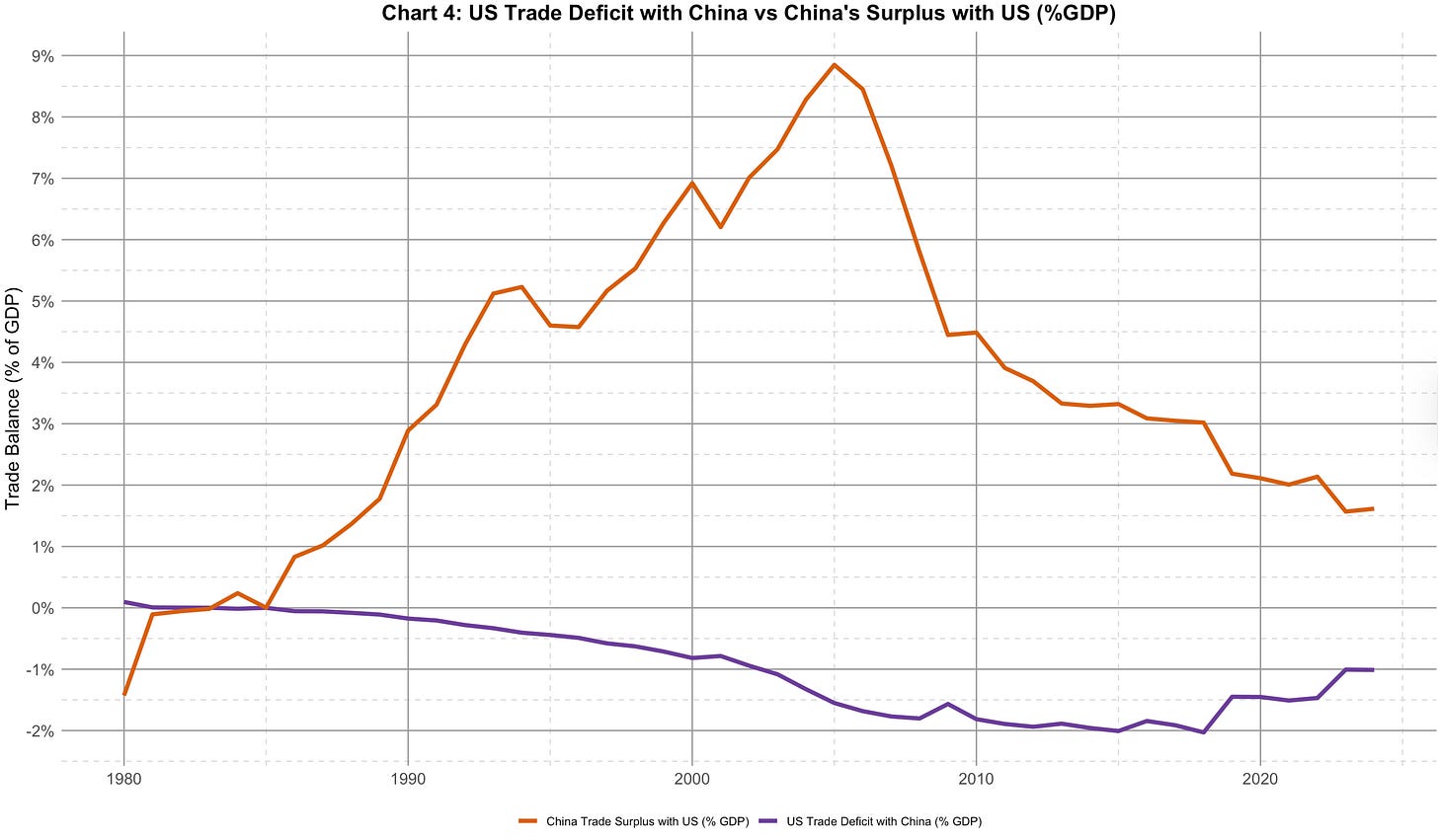

The U.S.-China trade and current account imbalances have been a defining feature of the global economy for decades (see Chart 3). They were at the core of the pre-2008 global financial crisis discussions on global imbalances and remain a key issue in today’s policy debates on tariffs and trade policies. These imbalances have not self-corrected, challenging simple economic frameworks that assume trade is naturally balanced over time. Chart 4 also shows the bilateral trade deficit between the U.S. and China in terms of their GDP.

In my previous discussion, I outlined two basic perspectives on trade: the static trade theory, which assumes balanced trade through price adjustments, and the intertemporal approach, where countries run trade deficits or surpluses to smooth consumption and investment over time. However, the persistence of U.S.-China imbalances suggests that these approaches alone are insufficient.

This raises the need for a framework where current account imbalances are not just temporary deviations but persistent, or even equilibrium, outcomes.

So far, I have abstracted from key structural elements of the international monetary and trade system that are essential to understanding why these imbalances are long-lasting. The complexity of the issue is obvious, but certain features must be incorporated into the analysis: the U.S. dollar’s role as the dominant global reserve currency, the United States’ position as the primary supplier of safe and liquid assets, and the asymmetries embedded within the international monetary system. These factors fundamentally challenge the functioning of the traditional models outlined above.

There are a few papers that I want to highlight here that indeed incorporate some of these features and are part of a rich literature that has addressed the logic of the pre-global financial crisis imbalances. In essence, they explain how persistent imbalances can emerge as a natural outcome of the international monetary system rather than a deviation from equilibrium.

Caballero, Fahri and Gourinchas (2008) “An Equilibrium Model of “Global Imbalances” and Low Interest Rates”

Dooley, Garber Folkers-Landau (2004) “The Revived Bretton Woods System”

Mendoza, Quadrini and Ríos-Rull (2009) “Financial Integration, Financial Development, and Global Imbalances”

Conclusions

To gain insight into today’s trade tensions, we must go beyond traditional trade theories and intertemporal models of the current account. While these frameworks offer useful insights, they fall short of explaining why some countries—like the U.S.—run persistent current account deficits while others—like China—accumulate sustained surpluses.

This highlights the crucial need for an economic framework that parsimoniously captures the essential features of the complex economic landscape, one that allows us to properly analyze:

(a) Why these imbalances persist,

(b) What their consequences are, and

(c) Whether and how policies should be designed to address them.

Without such a framework, we risk misunderstanding the causes of trade imbalances and implementing policies that fail to address the real underlying forces—or worse, create unintended disruptions in the global economy.

Thanks!

Thanks, Andrei. I plan to discuss this. Here, I was focusing just on the main approaches. In this older post (https://gianlucabenigno.substack.com/p/the-global-financial-resource-curse?r=nm3g) I anticipate some of the themes that I plan to discuss and relate to the Pettis-Klein view.