NOTE: This post is best viewed on a laptop, as some equations may be cut off on a mobile device.

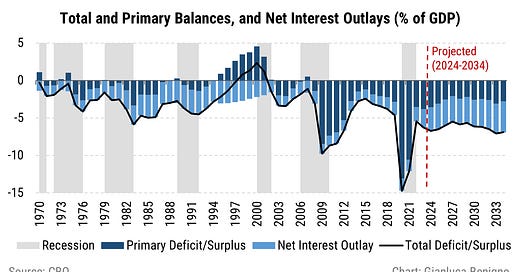

The U.S. economy is experiencing a fiscal deficit larger than any since the 1970s, except for the ones during and right after the global financial crisis. In this note, I will examine how the fiscal deficit is accounted for in the economy. Later, I will address other important questions, including the limits and consequences of fiscal deficits and the implications of their composition.

This first, of a series of notes, focuses on the interaction between monetary and fiscal policies. In this piece, I describe this link from an accounting perspective.

By focusing on the accounting of different fiscal operations, we conclude that:

Fiscal deficits are equivalent to Helicopter money insofar as they increase the net worth of the private sector.

From a private sector point of view, it does not matter if fiscal deficits are matched by an increase in the monetary base (reserves) or by issuing Treasuries: the effects on private net worth are equivalent.

It is important to note that at this level, I am not making any assumption regarding how the private sector reacts to the different fiscal operations.

In the next note of this series, I will expand on the monetary and fiscal policy interaction by focusing on the issues of fiscal capacity and fiscal backing.

Background

Most of the time in economic research, we study and examine fiscal and monetary policy as separate entities. In this note, I describe the institutional framework within which monetary and fiscal policy interact, focusing on the U.S. economy (a similar institutional arrangement holds also in Switzerland, for example).

Congress sets the fiscal policy in the U.S., while the Treasury decides how much debt to issue and its composition (bills, coupons, notes). The Treasury is the entity within the U.S. government that collects taxes.

TGA account

The first element through which monetary and fiscal policy are connected comes from the mechanics associated with the Treasury General Account.

What is the Treasury General Account (TGA)?

The Treasury General Account is the U.S. government’s operating account that is maintained by designated depositaries, primarily Federal Reserve Banks and their branches, to handle daily public money transactions. These transactions include deposits of taxes, customs duties, public debt receipts, proceeds from the sale of securities, and disbursements of U.S. Government payments.

Within this framework, the Treasury uses the TGA account to run most of its day-to-day business. The TGA account is managed by the New York Fed and it is where tax receipts and proceeds from the sale of Treasury debt flow.

When citizens or businesses receive a government cheque, they deposit it at their commercial bank, which presents it to the Fed. The Fed then debits the Treasury’s account and credits the commercial bank’s account at the Fed - increasing its reserve balance.

Therefore, the TGA enters the Fed’s balance sheet as a liability, along with notes, coins, and bank reserves.

A more detailed account is provided weekly from the Federal Reserve System (H.4.1 table)

In the next figure, we plot the evolution of the TGA in recent years. The TGA became a relevant component of the Federal Reserve Balance Sheet in the aftermath of the global financial crisis as the Federal Reserve engaged in quantitative easing and operated in an abundant reserve regime framework.

(a very interesting description of how the role of the TGA account evolved during 2008 is in Santoro (2012) and also the paper by S. Bell (Kelton) “Can Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending?” for a pre-GFC analysis).

The Treasury states in its refunding statement the size of the TGA. When the TGA is run down, the released liquidity will enter the financial system as reserve assets for commercial banks (balanced by deposit liabilities to non-banks), and deposit assets for non-banks.

The next graph represents the TGA account since its inception after the global financial crisis.

The operations conducted through the TGA account (the deposit and withdrawals) can be monitored daily (Daily Treasury Statement, DTS).

As we will visualize later, the Treasury pays the private sector when the TGA decreases. Thus, there is an increase in the reserves of commercial banks at the Federal Reserve, along with an increase in bank deposits corresponding to the target outlays of the private sector.

Budget Constraints and Balance Sheet identities

To understand the fiscal and monetary policy nexus, it is useful to review the standard identities at the level of the different actors that interact when a fiscal operation is implemented.

Let’s start by considering the accounting identity of Treasury and Central Bank balance sheets. We first examine the balance sheet of the Treasury. Total liabilities (debt issuance) are equal to the balance of the TGA account at the Central Bank.

Thus, from the government's point of view, changes in the balance of the TGA accounts are equal to revenues (taxes) – T(t) –, new debt issuance – B(t+1) – and transfers from the Central Bank – Transfer(t)-, minus outlays, –G(t) – and interest payment on past debt issued – (1+i)*B(t):

From the Central Bank's point of view, we have the following accounting balance sheet identity. The net worth of the Central Bank at a given period t is given by

Where A(t) denotes assets held at the Central Bank other than government securities, denoted with B(t) (here for simplicity bills and treasuries). On the liability side we have notes and coins (Cash), the balance on the TGA, and reserves R. Then, the flow budget constraint of the Central Bank is:

We now turn to the private sector (households and commercial banks)

We start by looking at the households (consumers) focusing on their balance sheets.

Where B(t) now denotes the private sector holdings of the bonds issued by the fiscal authority, D(t) are deposits held at commercial banks, A(t) are liabilities issued by the private sector (that could be interpreted as commercial paper or corporate bonds if we broaden the definition of the private sector), and L(t) denotes loans. NW(t) is the net worth of the private sector.

From the commercial banks’ point of view, we have the following balance sheet identity:

With A(t) denoting the commercial banks’ holding of liabilities issued by the private sector, B(t) represents the commercial banks’ holding of government-issued bonds, and L(t) represents the loans to the private sector.

In equilibrium we have

a) Loans market:

b) Private debt:

c) Government bond market:

d) Cash, Reserve, and Deposit Market clear as well.

We now consolidate the private sector balance sheet to obtain the following identity:

recall that:

And we can consolidate the public sector balance sheet (central bank plus Treasury) as

This last one is not an obvious step as it implies that the Central Bank is backing the Treasury. (see Chapter 1 of P. Benigno, “Monetary Economics and Policy”).

We can also combine the flow budget constraints of the fiscal authority and the Central Bank (substitute the transfer) to obtain

The consolidated budget flow identity accounts for how a fiscal position is adjusted based on changes in net government debt, changes in the monetary base (reserve plus cash) and changes in private asset holdings.

Fiscal Operations

Let’s now review some of the operations that involve the fiscal authority. We start by focusing on the case of helicopter money and then show how deficit spending produces similar effects.

Case I) Helicopter Money

From the accounting perspective, helicopter money involves directly distributing newly created money to individuals or households. This can take the form of direct cash transfers, tax rebates, or vouchers. For example, during Covid, the U.S. Treasuries issued cheques to American citizens.

We consider the case where there is enough balance in the TGA account. We would have the following set of transactions (again in blue bold)

In the next example, we will show that fiscal expenditure consisting of the government buying goods and services is equivalent to a transfer to the private sector as it increases the private sector's net worth. In the case of the helicopter money as a transfer of funds to the private sector, we have that the transfers are matched by an increase in the monetary base from a consolidated public sector’s point of view:

From a consolidated private sector’s point of view, this operation results in an increase in private wealth:

(note: since T>0 denotes taxes, -T denotes transfers).

Case II) Fiscal spending using TGA account balance.

Consider the following experiment: the Treasury buys medical equipment (G) from a pharmaceutical company for 100 billion USD (deposit check, D). This is an example of a fiscal expenditure using the balance in the TGA account.

Note that this operation increases the level of reserve in the banking system and increases net private wealth from the private sector point of view.

In terms of the previous identities, we have that from a consolidated public sector point of view.

The increase in public expenditure corresponds to an increase in the monetary base (i.e. reserves).

From a private sector point of view, the change in monetary base corresponds to a change in net worth:

Case III) Fiscal Spending Issuing Treasuries

Consider now the case in which there is not enough balance in the TGA account, and the Treasury decides to issue Treasuries to refill the TGA account and then buy the medical equipment from the pharmaceutical company.

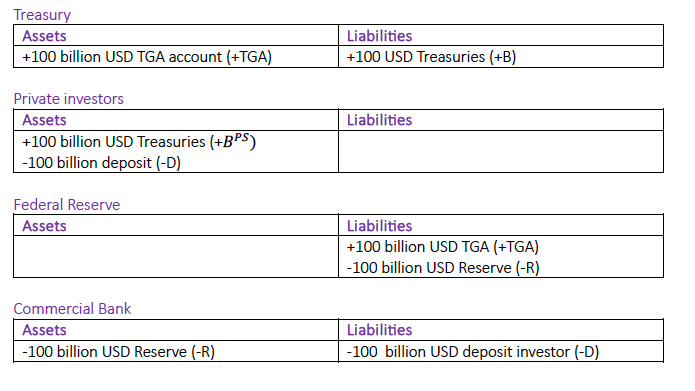

Let’s examine first the initial step of issuing Treasury and the refilling of the TGA account with Treasuries bought by private investors.

The refilling of the TGA with Treasuries (not bills, this might be important concerning the role of Money market funds and their use of the ON RRP facility in the case of the U.S. economy) results in a decrease in reserves. We assume that treasuries are bought by private investors. Assets at the level of the private investors shift from deposits (at commercial banks) to another asset (Treasuries).

From a commercial bank point of view, the withdrawal of deposits by private investors to purchase Treasuries is matched by a decrease in reserves at the Central Bank. Technically the Central Banks credit the TGA by the amount of Treasuries sold to the private sector and debit reserves by the corresponding amount at the commercial bank that has the account at the Federal Reserve. The balance sheet of the Federal Reserve does not change as one liability shifts into another liability.

This first step could be represented in terms of the previous equations from a consolidated public sector point of view.

While from a private sector point of view, we have the following consolidated balance sheet.

So, this operation results in a swap in assets from the perspective of the consolidated private sector.

Consider now the second step in which the Treasury engages with the pharmaceutical company to buy the medical equipment. In this second stage, there is no role for private investors, but another private actor comes into play (the pharmaceutical company). I denote in bold red the second step of the transaction.

As it is easy to note, the implications are the same as before in terms of private wealth net worth and reallocation of liabilities within the Federal Reserve but this time the financing is different.

Once we reframe all this within the accounting identities as above, we obtain:

The increase in public expenditure is now matched by the Treasury issuance of the corresponding debt amount.

From a private sector point of view, we have the following consolidated balance sheet.

The last two examples show how fiscal expenditure financed by an increase in monetary base or issuance of debt is equivalent to the helicopter money operation described in the first example.

While in this note I have focused on the accounting of fiscal operations, in the next note I will discuss the intertemporal implication of fiscal deficits.

Useful references:

P. Benigno (2024) “Monetary Economics and Policy”.

P. Benigno and S. Nistico (2020) “The Economics of Helicopter Money”.

J. Wang (www.fedguy.com): several blogs (see for example Debt Jubilee is already here).