Trump has demanded lower interest rates when the time is right. Current market pricing suggests a 25bps cut in 2025, while the Federal Reserve’s December Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) median forecast anticipates two cuts.

Background

In his speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos last Thursday, President Donald Trump said:

“ …I’m also going to ask Saudi Arabia and OPEC to bring down the cost of oil. You got to bring it down, which, frankly, I'm surprised they didn't do before the election. […] If the price came down, the Russia-Ukraine war would end immediately. Right now, the price is high enough. […]With oil prices going down, I'll demand that interest rates drop immediately. And, likewise, they should be dropping all over the world. Interest rates should follow us. All over, the progress that you're seeing is happening because of our historic victory in a recent presidential election”

In a follow-up interview on Friday, he reiterated his stance: "One way to stop it [the Russia-Ukraine conflict] quickly is for OPEC to stop making so much money and drop the price of oil ... that war will stop right away."

Trump’s remarks came just days ahead of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, scheduled for this Wednesday. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell will likely be asked to comment on Trump’s “demand” for lower interest rates. His response will probably emphasize that monetary policy decisions depend on the balance of risks between inflation and employment—the objectives of the Fed’s dual mandate—and that any adjustments will be guided by incoming economic data.

In this post, I examine the current trends in inflation and unemployment and assess whether these developments could push the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates beyond what markets currently anticipate. I conclude by discussing the potential benefits and risks associated with such a move.

My view consists of two main points (see also interview with MNI marketwatch):

No Significant Risks on the Unemployment Front

Under the fiscal primacy hypothesis, the probability of a recession in 2025 remains low. The economy is operating near full employment, so unemployment adjustments are likely supply-driven rather than demand-driven (see also: The Fed’s Trap and Fiscal Primacy).

Inflation’s Downward Trajectory might resume in Early 2025

Core CPI inflation has remained persistently above 3% in recent months. However, if we exclude owners' equivalent rent (OER), the harmonized consumer inflation measure (HCIP) currently runs at 2.3%. In early 2025, indicators suggest that rent-related inflation—accounting for approximately 36% of CPI—should moderate, leading to materially lower core services inflation. Additionally, further downward pressure on energy prices could reinforce this disinflationary trend.

Policy Implications

Absent major economic shocks, the combination of a healthy labor market and a possible benign disinflationary adjustment suggests that the Federal Reserve would be able to cut interest rates more aggressively than what markets are currently anticipating.

Current market pricing and Federal Reserve interest rate outlook

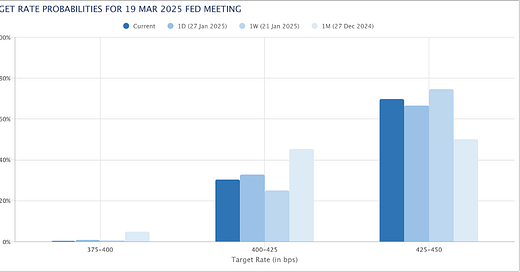

According to CME data, markets are currently pricing in a little more than one rate cut for 2025. In contrast, the December 2024 Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) showed that the median FOMC participant anticipated two cuts in 2025.

Trump's Davos speech did not have much effect on the Fed’s cut probabilities. In March, the Fed is still expected to hold the Fed funds rate at 4.37% with a probability of around 70%.

For May’s FOMC meeting, things are shaping up to be more interesting. Indeed, the probability of a 25 bps cut in May rose to over 40% as of Tuesday 28th of January.

A Contractionary Easing Cycle?

The Federal Reserve started its easing cycle in September 2024, reducing the Fed funds rate by a cumulative 100bps. However, rather than providing a net expansionary impulse, I argue that this cycle has been more contractionary than expansionary on balance.

A key distinguishing feature of this cycle has been the unusual increase in long-term yields despite rate cuts—rising from 3.7% on September 18, 2024, to 4.5% as of January 27, 2025. Additionally, the U.S. dollar has remained relatively strong, even after adjusting for the effects of the so-called “Trump trades.”

This combination—higher long-term yields and dollar strength—has counteracted the expected stimulative effects of rate cuts, making the overall financial conditions tighter than in a typical easing cycle.

This dynamic is particularly significant because the rise in nominal yields has been accompanied by a sizeable increase in real yields over the same period. Specifically, real yields (10-year yields) have climbed from 1.58% on September 18, 2024, to 2.2% as of January 24, 2025.

Such an increase in real yields suggests a tightening of financial conditions, effectively offsetting the stimulative intent of the easing cycle. (see also Kashkari on this)

This suggests that overall the stance of monetary policy has not changed much despite the cumulative 100bps cut in the Federal fund rate.

Moreover, lowering interest rates typically reduces interest income received by the private sector while simultaneously decreasing interest outlays from the public sector, thereby narrowing the overall fiscal deficit (see

and ; also a Bloomberg article here).Why, then, have we observed such a pronounced steepening of the yield curve?

To be brief, my preferred explanation is that the Federal Reserve initiated the easing cycle primarily out of concern for unemployment—which, once again, has not materialized as a major issue—while inflation remained well above target. This policy stance led markets to price in structurally higher interest rates in the future, contributing to the increase in long-term yields. With the ex-post insight, there was no need for the Fed to cut the Fed funds rate by as much as 100bps.

In contrast, my view is that if rate cuts were implemented alongside a clearer improvement in the inflation outlook, long-term yields would likely decline.

An interesting alternative perspective suggests that this “reverse conundrum” (i.e. the increase in long-term yield while cutting short-term interest rates) can be explained by a sharp decline in foreign official demand for US Treasuries and a likely shift towards gold (Ahmed and Rebucci).

Unemployment and Inflation Outlook

Back in March 2024, I discussed the implications of persistent U.S. fiscal deficits, introducing what I termed the “Fiscal Primacy Hypothesis” (see: The Fed’s Trap and Fiscal Primacy). At the time I argued that the U.S. economy has entered a structurally different phase, largely driven by fiscal policy.

I stated:

My hypothesis, therefore, suggests that the U.S. economy has entered a new phase, largely due to fiscal interventions. This new macroeconomic norm differs from the one before the pandemic. Previously, the equilibrium was marked by modest productivity growth at an average of 1.4% per year, real GDP growth hovering around 2%, and unemployment around 4%. If we're now experiencing productivity rising above 2%, this could imply that the trend growth has shifted upwards to about 2.5%, with a natural unemployment rate similar to the level before the pandemic. In this context, the natural interest rate would stand higher, around 1.5% in real terms, which would be equivalent to an equilibrium nominal rate of about 3.5%. In this scenario, current monetary policy may not be restrictive, regardless of how current real interest rates are calculated. Finally, higher productivity could be well consistent with nominal wages growing at least 4 % per year.

One important qualification of the fiscal primacy hypothesis is that monetary policy’s ability to affect aggregate demand is now more limited. This is due to a muted transmission mechanism to consumers, for example, because of the long-term duration of the mortgage and, more generally, because fiscal policy has a more direct impact on demand.

I plan to discuss and expand more on the fiscal primacy hypothesis in another blog, but for now, let’s focus on the unemployment and the inflation outlook.

The chart below illustrates the recent trend in unemployment. In July 2023, unemployment reached a low of 3.5%. Since then, most of the increase in unemployment has been driven by rising labor supply, which expanded from 167K to around 168K. Interestingly, employment (the green line) has stabilized at around 161K since July 2023, signaling an economy that is operating at full employment.

On the inflation side, I will focus on core CPI, the rent of shelter component of CPI, and the HICP that excludes the owner occupier’s rent from the CPI.

Owner’s Equivalent Rent (OER) accounts for 27% of the total weight in overall CPI. If we exclude it from the computation, year-over-year CPI would stand at 2.6%, lower than the 2.9% headline rate.

Over the past two years, month-on-month OER readings have moderated gradually. However, when we combine this trend with data on new rental agreements, the evidence suggests that further moderation is likely in 2025. This would contribute to a continued decline in core inflation, reinforcing expectations of a more benign inflation environment for 2025.

Costs/Benefits of Cutting Rates

While the inflation outlook suggests moderation, several risks remain. Many commentators have mentioned the potential inflationary impact of Trump’s new tariffs. Additionally, adverse geopolitical development could put upward pressure on energy prices, complicating the disinflationary trend.

Here I would like to emphasize the following implications:

a) Potential Benefits of Rate Cuts

If rate cuts occur alongside an improving inflation outlook, they could ease financial conditions and support economic momentum. Specifically:

Refinancing benefits: Lower interest rates would support both corporate and household refinancing cycles, particularly if short-term rate cuts are accompanied by a decline in long-term yields.

Financial stability: From a financial stability perspective, lowering the policy rate now reduces the risk of the economy hitting R** (see Benigno et al, 2024; and Benigno et al, 2020), which could otherwise trigger financial stress.

b) Risks of Rate Cuts

Besides the fiscal implication discussed earlier:

Tightening Global Financial Conditions: On the risk side, a key concern is the potential reignition of the Yen-Carry Trade feedback loop (see “The Bank of Japan's Put”). In August 2024, this loop was set off by a hawkish Bank of Japan (BoJ) stance alongside rising U.S. recession risks. If the Federal Reserve were to implement an unjustifiably aggressive rate cut, it could inadvertently tighten global financial conditions, ultimately spilling back into U.S. financial conditions, as seen in August. Similarly, a sharp stock market correction could trigger a comparable mechanism, leading to a similar unwinding of the yen-carry trade position.

Indeed, sharp movements in the JPY-USD exchange rate play a central role in shaping global financial conditions. A disorderly unwinding of carry trades could amplify market volatility, which would have broader implications globally and also in the U.S. economy.

Conclusions

Trump has demanded lower interest rates, framing it as a necessary step when the time is right. However, monetary policy decisions remain contingent on inflation, employment, and broader financial conditions.

In this analysis, I have argued that interest rates in the U.S. could fall further than what markets are currently expecting and even beyond the Federal Reserve’s projections.

My baseline (contingent on no shock) is that:

Disinflationary trends will continue into 2025, particularly as owner’s equivalent rent moderates and broader core inflation eases below 3%.

Labor market conditions will remain strong, with any rise in unemployment driven more by supply-side factors than by demand contraction.

The Federal Reserve may cut rates more than what is currently being priced by the market and its own latest median forecast.