The Bank of England at a Crossroads: Rethinking the Narrative Before It’s Too Late?

On the need of shifting gear

Today’s policy decision, along with the Bank of England’s updated projections, reinforces the need to rethink the narrative shaping its monetary policy.

My suggested narrative focuses on the mortgage resetting channel and the need to prevent a demand contraction, a challenge further exacerbated by insufficient support from fiscal policy.

Key takeaways:

Two major outcomes from the latest BoE meeting: a split vote and the emergence of support for a 50bps cut. The forecast—based on market pricing (two cuts)—points to higher inflation and lower growth in 2025.

I argue for a revised narrative that acknowledges both the lack of fiscal stimulus and the consequences of past rate hikes which in turn:

a) have contributed to increasing rental inflation and its persistence in the system.

b) are set to impact spending through the mortgage resetting channel, creating a demand drag.

Aggressive cutting would mitigate the mortgage reset shock, cushion aggregate demand, and gradually contribute to lower rental inflation later this year and beyond.

The Decision

As widely expected, the Bank of England cut the Bank Rate by 25bps to 4.5%.

In my opinion, the big surprise was the 7-2 vote where Dhingra and Mann voted for a 50bps cut. This was particularly unexpected given that Mann has consistently been on the hawkish end of the BoE spectrum.

The two dissenters, though, have different views on inflation dynamics:

a) Mann (my attribution): a more activist approach at this meeting would give a clearer signal of financial conditions appropriate for the United Kingdom, even as monetary policy would need to remain restrictive for some time to anchor inflation expectations, and Bank Rate would likely stay high given structural persistence and macroeconomic volatility.

b) Dhingra (my attribution): the subdued outlook for demand remained consistent with CPI inflation staying sustainably at the target in the medium term despite the expected near-term uptick in regulated prices, and Bank Rate needed to account for policy transmission and supply capacity over the medium term.

In what follows I provide an update on the voting pattern (which is public) and offer a tentative positioning of each member within the three-scenario framework I have previously discussed (“The Bank of England Wimbledon’s Edition” and “Scenario Analysis as a New Communication Device for Central Banking”)

I have kept Mann aligned with the third scenario, as she still alludes to “structural persistence” in inflation. However, her 50bps vote suggests that she associates rate cuts primarily with financial conditions being too tight, despite acknowledging inflationary persistence.

Another key takeaway from the monetary policy summary is the reinforcement of a gradual approach to easing monetary policy restrictiveness.

"Based on the Committee’s evolving view of the medium-term outlook for inflation, a gradual and careful [my emphasis] approach to the further withdrawal of monetary policy restraint was appropriate."

Additionally, there was a more explicit focus on the balance between demand and supply in driving inflation. This builds on recent speeches by Breeden and Taylor, with Breeden, in particular, elaborating on how to assess this balance in practice.

"In addition to the risks around inflation persistence, there were also uncertainties around the trajectories of both demand and supply in the economy that could have implications for monetary policy. Should there be greater or longer-lasting weakness in demand relative to supply, this could push down on inflationary pressures, warranting a less restrictive path of Bank Rate. If there were to be more constrained supply relative to demand, this could sustain domestic price and wage pressures, consistent with a relatively tighter monetary policy path."

The Current Economic Outlook and What is Next?

I will now briefly discuss the economic outlook and the updated forecast from the Bank of England, with a focus on GDP and CPI projections. Specifically, I will compare the November and February Monetary Policy Reports, examining one-year-ahead forecasts, though the Bank of England extends its projections further over the policy horizon.

I also report the projection conditional on a constant interest rate (based on the report).

The different forecasts are not directly comparable due to varying conditioning assumptions, notably higher gas prices between the two projections. However, we can still draw some key implications.

GDP growth is significantly weaker compared to the November forecast. Even with a 4.75% interest rate, GDP growth was previously projected to be much stronger than the current February projections, at lower interest rates (both market-based and the current 4.5% rate).

This suggests a deterioration in the economic outlook, independent of other conditioning factors.

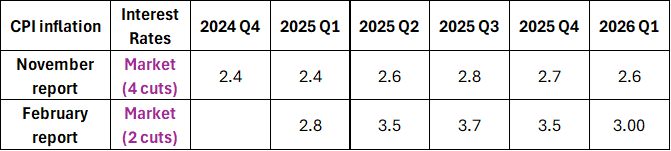

Regarding inflation, we have the following updated forecasts.

The CPI projections at constant interest rates are as follows:

The upward revision of the inflation projections is quite notable. In the November forecast, with a constant interest rate of 4.75% (higher than the current 4.5%), inflation was projected to be significantly lower than in the latest projections.

This shift is largely driven by:

The reversal of energy prices, now making a marginally positive contribution to inflation.

The increases in goods and food prices, further worsen the inflation outlook.

Chris Marsh at ExanteData recently published an insightful blog suggesting that fiscal policy is not providing meaningful support to aggregate demand—even in the short run—as it had been anticipated in November.

Based on the BOE’s projections, the U.K. economy appears to be heading towards a lower growth/higher inflation outcome in 2025.

Mortgage Resetting, Aggregate Demand and Inflation

In one of my first posts on the economic outlook for the U.K. economy, I emphasized the “Catch-22 effect” (see also FT Alphaville) and stated the following:

“As we navigate through 2024 there are two main risks:

A squeeze on disposable income that could put downward pressure on consumption.

Further stickiness in inflation arising from persistently higher rental price inflation.

However, since major central banks are tilting towards a cutting cycle, the BoE should be comfortable in cutting rates to avoid further inflationary pressures and in alleviating the pressure on households coming from higher interest rates.”

With the Bank of England having now cut interest rates by 75bps from its peak, it is reasonable to assume that we should observe moderation in housing rental costs in 2025.

Concerning the squeeze on disposable income, I here report a paragraph from the November 2024 Financial Stability Report:

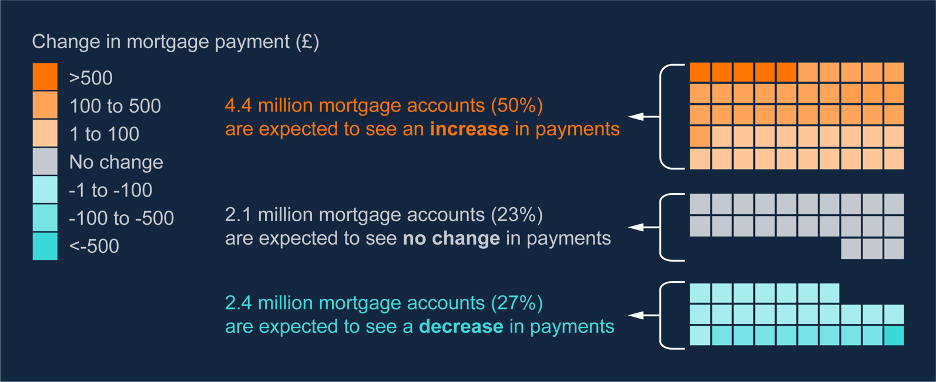

37% of fixed-rate mortgage accounts have not yet re-fixed since rates started to rise in 2021 H2, so the full impact of higher interest rates has not yet passed through to all mortgagors. Between December 2024 and 2027 Q4, around 50% of mortgage accounts (4.4 million) are expected to refinance onto higher rates (orange squares in Chart 4.2). Of these, 2.7 million (31% of all mortgages) are expected to refinance onto a rate above 3% for the first time and roughly 420,000 (5% of all mortgages) will see payments increase by more than £500 per month.

This data emphasizes the ongoing challenges for households, particularly as mortgage resets continue to impact disposable incomes. While rate cuts should help ease some of these pressures, the transition may still weigh on consumption dynamics in the near term given that the Bank Rate has increased quite significantly from its lows.

Looking ahead, indicators of household spending will be crucial for assessing the status of aggregate demand. In the February Monetary Policy report the Bank of England notes:

Having grown steadily in the first three quarters of 2024, more recent indicators of household spending have weakened. Retail sales fell by 0.8% in 2024 Q4. Alongside that, consumer confidence has been weak around the turn of the year. The headline GfK measure fell sharply in January (left panel, Chart 2.13), to its lowest level since December 2023, while the S&P UK Consumer Sentiment Index also fell notably. Savings intentions, according to the GfK survey, remain very elevated. However, surveys of consumer confidence are not always reliable predictors of household consumption.

Household consumption growth is expected to be flat in 2024 Q4 before picking up slightly to 0.2% in 2025 Q1. That is weaker than expected at the time of the November Report and broadly consistent with intelligence from the Bank’s Agents network where consumer-facing firms also report subdued levels of demand. Beyond that, consumption growth is expected to pick up further over this year, supported by a declining saving ratio and a reduced drag from past interest rate rises.

I suspect that the projected increase in food and energy prices may limit the effect the Bank of England expects from a declining saving ratio and a reduced drag from past interest rate hikes.

Given the lack of fiscal support (as Chris Marsh also notes), the Bank of England's narrative could shift toward engineering economic support by closely monitoring:

a) Household spending – which is directly affected by Bank Rate changes through variable mortgage rates and mortgage resets.

b) Rental costs, where monetary policy has a delayed but direct impact.

Without fiscal intervention, the inflationary pressures projected for 2025—stemming from food and energy prices and their impact on disposable income (i.e. those are core consumption items)—would be better offset by lower interest rates through these two channels.

As I have argued in previous posts, service inflation is naturally stickier due to slower price resets and largely reflects the propagation of past supply shocks. Wage inflation, meanwhile, has been catching up with the loss of purchasing power. If anything, wages have served as a cushion for households against both supply shocks and rising interest rates.

Conclusions

At the latest monetary policy meeting, two MPC members voted for a 50bps rate cut. In his most recent speech, Alan Taylor signaled a preference for a more accommodative stance than current market pricing suggests. A stronger emphasis on aggregate demand could justify a more aggressive easing of policy. Given the outlook, monetary policy should lean toward accommodation rather than remaining in restrictive territory. I spare here the discussion on r*.

Great as usual, adding to the mortgage channel you also have big corp debt rollovers (the market based finance figures are quite scary for 25/26)

Adding a challenge to forecasting the outlook are the HH level differences in debt vs savings (the core of the rate hikes are stimulative arg I am v much against). Around 40% of HHs are home owners mortgage free, so will not be a victim of rollovers/haven’t been hit by cuts at all, whereas those that are going to get hit will get hit quite hard. On a non mon pol note, another terrible hit for wealth inequality!