The Flip Side of UK Monetary Policy

This note draws from remarks I delivered as part of the monetary policy outlook panel at the Bank of England Watchers’ Conference.

This note reflects on a series of observations that, I believe, warrant greater attention in the current debate on UK inflation and monetary policy. Although inflation has been declining, the disinflation process remains uneven and sluggish, shaped by a set of factors that render the UK experience notably distinct.

In my opinion, capturing these factors is crucial for assessing the monetary policy stance and its desirable path going forward.

Understanding how monetary policy transmits through the economy is, in my opinion, a non-trivial task in macroeconomic analysis. Transmission is not mechanical — it depends on state-contingent factors such as the stance of fiscal policy or institutional features, like the structure of the mortgage market. But crucially, it also depends on the policy itself. The rapid and sizeable increase in the UK policy rate is part of the propagation mechanism. I argue here that the pace and magnitude of the tightening have activated a cost channel, whereby the mechanics of monetary transmission have reinforced, rather than dampened, inflationary pressures in the short term.

In this blog, I will focus on three aspects in particular.

The role of Housing in UK inflation:

Main claim: Housing inflation can be a key factor in affecting the persistence of service inflation and more general headline inflation.

The Drivers of UK Inflation:

Main claim: A sizable and rapid increase in nominal interest rates has activated the cost channel.

The flip side of nominal wage growth:

Main claim: Wages are not just a cost to firms; they are also income to workers, and thus support consumption.

Given my previous considerations, I will conclude by offering my thoughts on the monetary policy outlook.

Related Blogs:

The Bank of England at a Crossroads: Rethinking the Narrative Before It’s Too Late? (related post);

Scenario Analysis as Communication Device for Central Banking (related post);

A Quasi-Global Inflation Overview (related post);

Has Wage Growth Fueled Inflation in the UK? (related post);

At the Core of UK Inflation (construction of supercore inflation and supercore wage index);

FT Alphaville on Catch-22 (short version of the Catch-22 effect);

Is the Bank of England in a Catch-22 Situation? (long version of the Catch-22 effect);

Classic Paper on the Cost Channel in the context of the New Keynesian approach is “Optimal Monetary Policy with the Cost Channel” by F.Ravenna and C. Walsh.

The Specificity of UK Inflation: Housing Inflation as a Key Driver of Inflation Persistence

The first and perhaps most overlooked feature of UK inflation is the sharp and persistent rise in actual housing rents. The peak of actual rents for housing was reached in January with 7.8% YoY. This component has become a major driver of headline CPI, and yet it is often under-discussed in high-level policy narratives.

The following chart compares rent inflation across countries1. The UK currently records the highest level of rent inflation, having peaked more recently than in other economies.

Why does this matter? Housing costs affect the economy on multiple levels. For households, rent is a major and inelastic component of the consumption basket. Increases in rent directly squeeze disposable income and shape inflation expectations. But beyond the consumer channel, rising rents also affect businesses. Many service-sector firms lease commercial space, and rising rents increase their overhead costs. In this way, housing becomes a conduit for broader cost pressures.

Importantly, in the UK, many landlords are buy-to-let investors who have seen their mortgage rates rise sharply over the past years. With refinancing costs higher, landlords pass on those costs to tenants, including commercial tenants. This sets in a mechanism where monetary tightening translates into higher shelter costs, which in turn drive inflation persistence in services.

This is the "flip side" of policy: tightening intended to reduce inflation ends up, in part, sustaining it. In previous posts, I referred to this mechanism as “Catch-22” and back in February last year, I expected this component of inflation to increase through 2024 based on the aforementioned logic.

Background: What Has Driven UK Inflation? Supply Shocks and Policy Propagation

Like many advanced economies, the UK has experienced a surge in inflation due to global supply shocks. Energy prices, food prices, and supply chain disruptions have all played a role. But what is striking in the UK context is the continued strength of these effects through propagation channels.

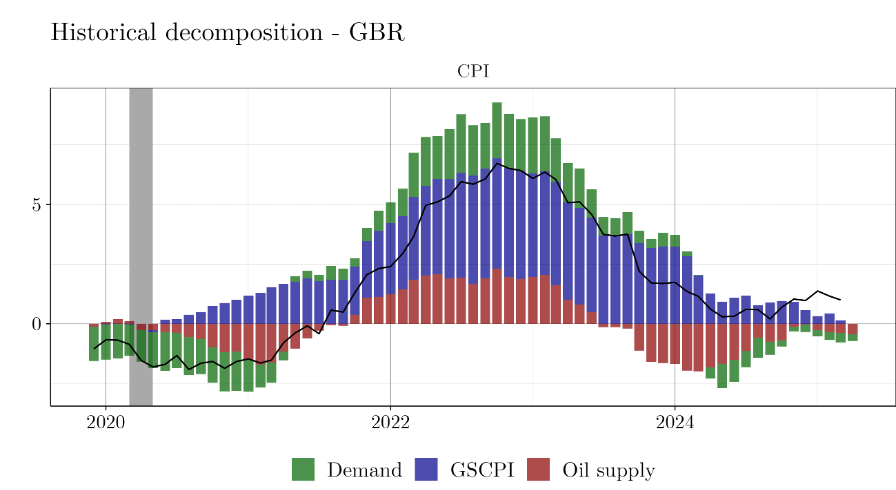

The following decomposition is based on Akinci, Benigno, Clark, and Koechlin’s “Global Inflation Shocks”. It attributes deviations of UK CPI inflation from its historical mean to a set of identified global factors—specifically, shocks to the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, global demand pressures, and oil supply. This framework allows us to quantify the relative contribution of global external inflationary forces to recent UK price dynamics.

A decomposition of global components shows a substantial role for supply-driven inflation, even as headline figures ease. This persistence reflects second-round effects, input-cost pressures, and sectoral pass-through dynamics. What is interesting is that, in the latest part of the sample, these components account for relatively small fluctuations of CPI inflation.

Here, I suggest that there is another “shock” worth considering: monetary policy itself.

The pace and magnitude of Bank Rate hikes in the UK have been unusually steep by its historical standards. Within the span of less than two years, the UK policy rate has risen from 0.1% to levels exceeding 5%.

Such a sharp and rapid tightening acts almost like a nonlinear shock, with asymmetric effects. One such effect is the activation of the cost channel. As we can see in the following chart, other central banks have also tightened monetary policy rapidly and by similar magnitudes, but as noted earlier, the transmission mechanism differs significantly due to institutional features, particularly in the rental property market and mortgage structure.

The UK Bank Rate is currently the highest among advanced economies and has declined more slowly than in the United States.

In the United States, the dominant use of 30-year fixed-rate mortgages—including for many investment properties—has substantially muted the transmission of higher policy rates to both homeowners and landlords. Additionally, U.S. tax policy remains highly favourable to rental investors, including full deductibility of mortgage interest. As a result, the rental property channel has remained relatively insulated from rate hikes. In contrast, Canada’s rental property market is dominated by individual investors holding shorter-term or variable-rate mortgages, often with terms of five years or less. This structure makes Canadian landlords highly sensitive to refinancing costs, and it has amplified the impact of rate increases on rental supply and cash flow. The earlier and more aggressive cutting cycle by the Bank of Canada could indeed explain why the rental component in inflation has declined more rapidly in Canada relative to the UK. In the UK, the rental property channel is even more exposed: not only are mortgage terms typically short (2–5 years), but the buy-to-let sector is large and highly leveraged, with many landlords reliant on frequent refinancing. Moreover, recent UK tax and regulatory reforms—including the phase-out of mortgage interest deductibility and higher stamp duties—have compounded the impact of rate hikes on landlords’ net yields.

As a result, monetary tightening in the UK has transmitted more forcefully through the rental property channel than in the United States, reinforcing the inflationary impulse.

In short, in the UK, the sizeable and rapid increase in policy rates has increased mortgage costs, especially for variable-rate or recently refinanced loans. Landlords, as noted, have passed these higher costs onto tenants. But those tenants include businesses, especially in the services sector. The result is that tighter monetary policy ends up raising input costs for service providers, sustaining inflation in the very sectors that are supposed to moderate under policy tightening.

This propagation mechanism is rarely emphasised in mainstream discussions of policy transmission. Yet it may be one of the reasons why UK services inflation remains sticky and more resistant to the disinflation observed elsewhere.

What about Nominal Wages? Not a Cost Shock, But a Demand Support

A third important dimension of the UK inflation debate concerns wages. Much of the conventional narrative treats wages as a potential source of inflationary pressure. In its newly adopted scenario analysis, the Bank of England has put a lot of emphasis on the growth rate of nominal wages as a driving force of service inflation and its persistence. Here, I argue that in the current UK context, this might not be the case.

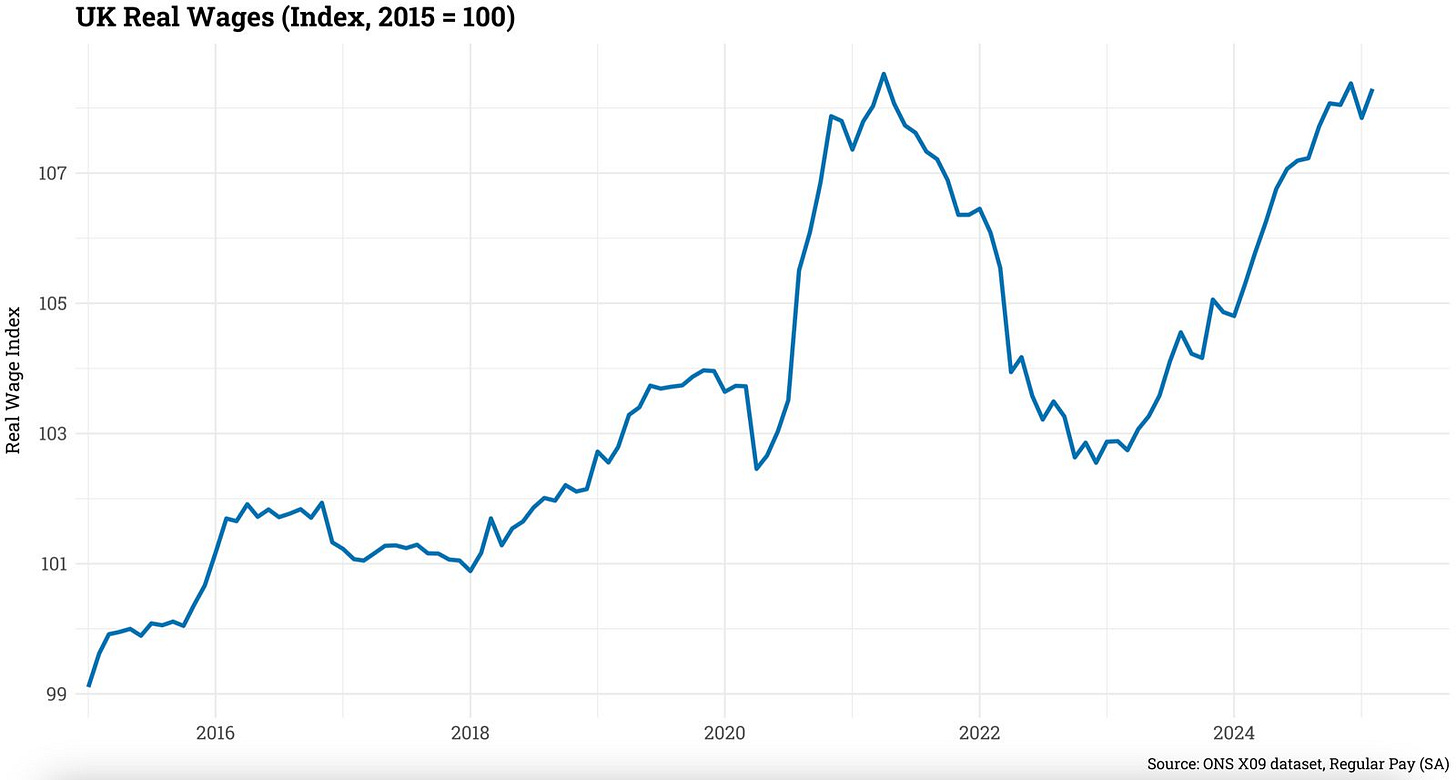

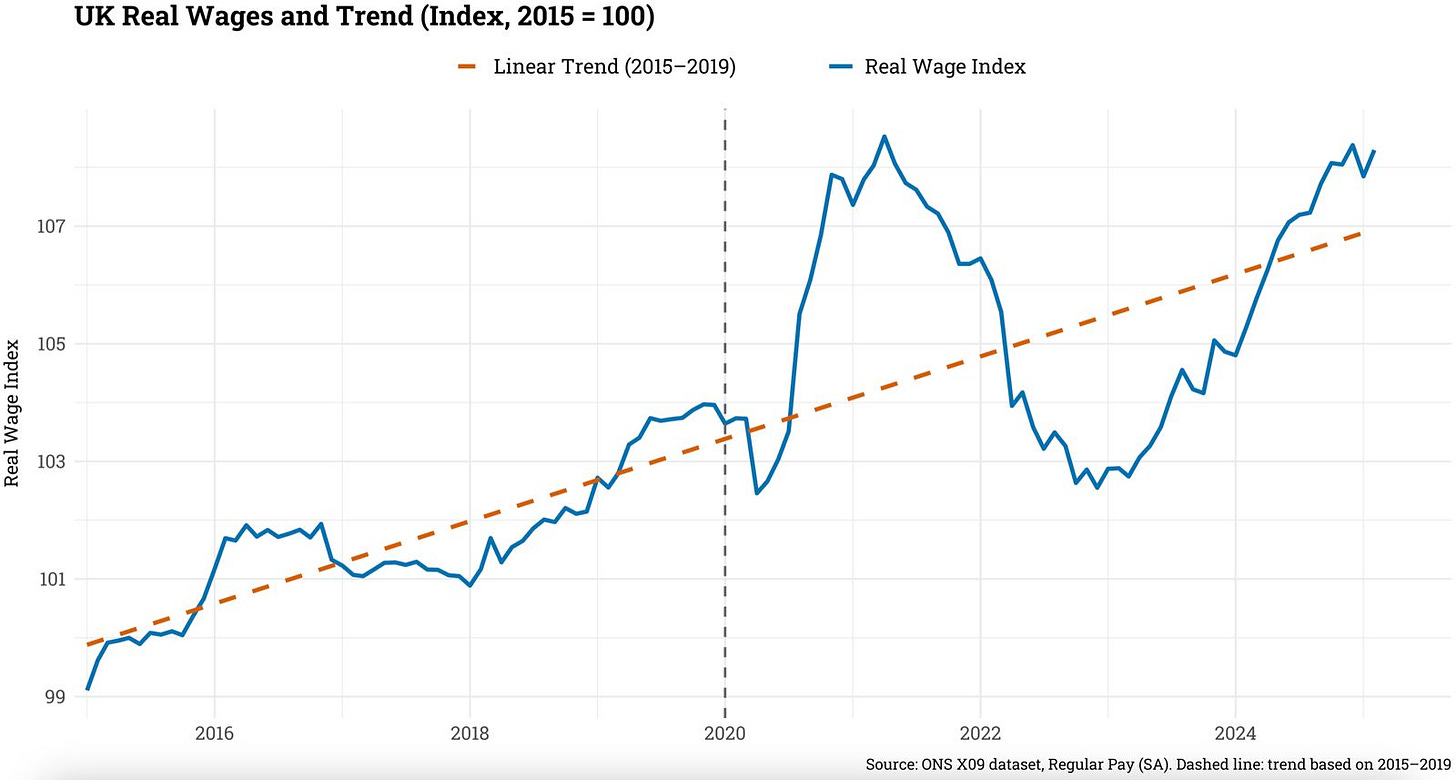

To put things in perspective, let’s first examine the behavior of real wages over time. Real wages in the UK remain low by historical standards. They have only recently returned to levels just above their pre-pandemic trend, and they are still below levels observed before the global financial crisis. When seen in this light, recent wage growth appears more like a process of normalisation than overheating.

If we focus on wage behavior post 2015, where we observe a steady increase in real wages, we note that currently, real wages are just above the implied 2020-2025 trend.

The flip side of wages is that they should not only be seen as input in the production process, but also as income from a household perspective. In an economic context characterized by a stagnating economy, nominal wage growth, rather than fuelling inflation, played a supporting role for aggregate demand. It has helped households cope with the cost-of-living crisis by sustaining consumption in the face of high energy prices, rising rents, and food inflation. Wages have functioned as a demand support, not as an inflation driver.

In a previous blog (“Has Wage Growth Fueld Inflation in the UK?” ), I have argued that the link between wages and prices appears weak in the current cycle, and the labour market may be operating under dynamics not well captured by traditional Phillips curve logic. Post-COVID sectoral shifts, labor market participation changes, and compositional effects all point to a need for updating how we think about wage inflation, at least in the post-COVID context.

Implications for Monetary Policy: The Flip Side

Taking these elements together — the housing channel, the propagation of policy-driven cost shocks, and the stabilising role of wages — a different view of the UK inflation process emerges. This has important implications for monetary policy.

Keeping interest rates elevated in an environment where inflation is already moderating risks reinforcing the very persistence that policymakers aim to avoid. By feeding through to rents and business costs, high rates may act as a source of inflation inertia. Meanwhile, concerns about wage-driven inflation appear overstated, and nominal wages have just caught up with the cost of living.

What are the possible side effects of a more “activist” easing cycle by the Bank of England?

One potential risk is that a depreciation of the pound could import inflation through higher goods prices. While this remains a possibility, I would argue that the risk is currently limited. Given the easing bias among advanced economy central banks—and the more aggressive easing cycle already underway at the ECB (Euro area being the more relevant trading partner from the UK’s perspective)—the relative stance of UK monetary policy is unlikely to exert strong downward pressure on sterling. Recent market turmoil linked to U.S. tariff announcements has not led to a weakening of the pound. Combined with lower energy prices, the current environment may actually support a more aggressive easing cycle.

There is also a fiscal dimension to consider. A more aggressive pace of easing could help reduce the Bank of England’s balance sheet losses and, in turn, lower the associated fiscal costs.

Overall, this calls for a reassessment of the policy stance. The Bank of England does not need to be gradual and cautious. It should adopt a more deliberate shift toward easing that could help unwind the cost-channel effects of past tightening, without undermining the broader disinflationary trend. That is the flip side of UK monetary policy.

All series are the rent component of the country’s CPI: BLS Code: CUUR0000SEHA (Rent of Primary Residence), ECB statistical data code: ICP.M.U2.N.041000.4.ANR (Actual Rent for Housing), ONS code: D7GQ (Actual Rent for Housing), e-stat code: @cat01: 0046 (Rent), Statistics Canada: Shelter subcategory: Rent, SFO code: 100_4002 (Housing Rental)

Terrific! Central banks are stuck in linear models while the world functions in Complexity.

Thanks, Malcolm, for your comment! I think is the change that makes the problem more acute. Imagine you are a landlord with a mortgage, you will be more willing to pass on the cost of higher interest rates in that case than when the increase in interest rates is spread over time. In the latter, you will do that too, but the pass-through might be smaller for the same increase. (i.e., I am implicitly suggesting that pass-through is non-linear). Regarding your second point, you might want to take into account that affordability in buying properties might be affected by higher interest rates too, so limiting that option, unless you buy with cash. This channel might actually increase the demand for rental properties by crowding out buyers, indeed.