A Quasi-Global Inflation Overview

A review of the key inflation trends among advanced economies and some policy implications

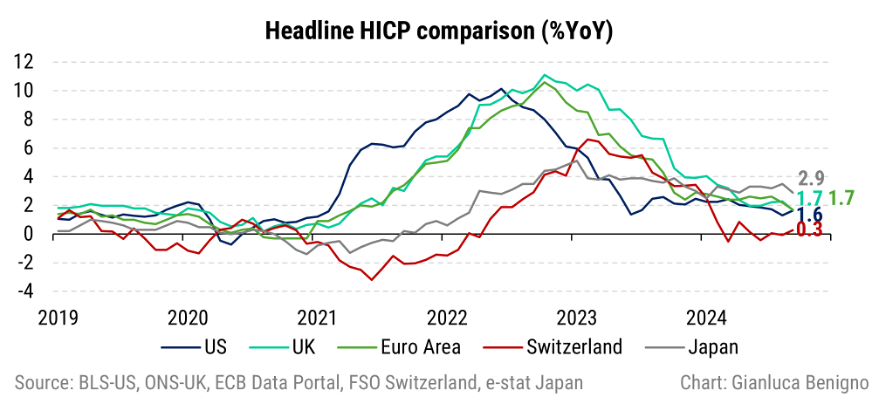

The previous graph illustrates that, for a selected group of advanced central banks, current inflation measures are relatively close to their target levels, which might suggest a return to pre-pandemic patterns. However, in this blog, I argue that this interpretation could be misleading.

Related Posts

Japan September-24 CPI Inflation Report (inflation report);

UK September-24 CPI Inflation Report (inflation report);

September-24 U.S. CPI Inflation report (inflation report);

Switzerland September-24 CPI Inflation Report (inflation report);

The Inflation Myth (related post).

Background

In our monthly reports (see the links above for the latest releases), we analyze inflation trends across selected individual countries, focusing on key inflation measures. I try to highlight the key developments in inflation, emphasizing the importance of understanding not only the headline measures targeted by central banks but also various underlying components driving inflation dynamics. Indeed, the pandemic and the following recovery have underscored the need to consider the different drivers of inflation. This is particularly relevant as the appropriate monetary policy response depends on its transmission mechanisms (i.e., which sectors it affects and how) and on the nature of the economic shocks. In this sense a more granular picture is crucial.

Though it may feel like a distant memory, Fed Chair Powell once emphasized the need to focus on supercore inflation (for details, refer to this Fed blog and this previous FOMC press conference on the role of supercore). Similarly, President Williams used the 'onion' analogy (see here) to describe the different layers of inflation dynamics. Currently, the Bank of England and the ECB are particularly concerned about the persistence of service-sector inflation.

In this post, I provide a cross-country analysis of these inflation measures and discuss potential policy implications. We focus on HICP and CPI: Core, Goods, and Services measures.

Key Takeaways

Focusing on different measures of inflation I would like to emphasize the following:

Post-Pandemic Dispersion: The current inflationary environment is quite different from the pre-pandemic period, with greater dispersion across countries in various inflation measures. This suggests that inflation dynamics are more diverse than before.

Policy Challenges Ahead: The variation and heterogeneity in inflation measures across countries imply different policy challenges moving forward. Central banks will need to tailor their strategies to address their unique inflation dynamics. For example, in previous blogs, I emphasized the Catch-22 effect as a key feature for the understanding of the Swiss and UK services inflation.

Impact of Major Shocks: Two key shocks have shaped the current landscape: disruptions to the global supply chain (GSCPI) and energy price shocks. The way these shocks propagate through economies depends heavily on the policy response—both monetary and fiscal—, and on the structural characteristics of each economy. For example, in the case of Switzerland, the active use of FX intervention aimed at keeping the Swiss Franc strong has muted the impact of these shocks (see The SNB’s Forward-Looking Compromise).

Need for Multilateral Perspective: Except for the US (and the Fed), formulating an effective policy response requires moving beyond a single-country focus. This highlights the importance of developing research and policy frameworks that account for structural heterogeneity and interconnections between economies. In this respect, I emphasized in the Bank of Japan’s Put the role of the Yen carry trade as a constraint to monetary policy normalization for the Bank of Japan.

Headline and Core

Let’s start by looking at headline and core inflation measures.

We begin with the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) as a common benchmark across countries. Unlike other measures, HICP excludes owner-occupied housing costs. Japan, while avoiding significant inflation peaks during this period (mostly staying below 3%), currently has the highest HICP inflation among the countries analyzed. In contrast, Switzerland has experienced near-deflationary HICP levels throughout much of 2024.

However, when we focus on core inflation measures, which maintain owner-occupied housing costs, but exclude volatile components, namely energy and food, a different pattern emerges. Across countries, we observe greater dispersion in core inflation levels. Notably, core inflation in both the UK and the US remains persistently above 3%, reflecting underlying price pressures. In these countries, the decline in core inflation has stalled in recent months, a trend that is especially apparent in the US. In contrast, Switzerland and Japan have not experienced the same peaks in core inflation as seen in other countries, maintaining more moderate levels throughout this period.

Compared to the pre-pandemic period, we see significant differences: as a common feature, all measures are higher than pre-pandemic, but, on the other hand, the dispersion across countries has become more pronounced.

Goods and Services

To enhance our investigation into inflation trends, it is crucial, in my view, to analyze the dynamics of goods versus services inflation. At first pass, the most immediate effects of global supply chain disruptions and energy price shocks are likely to be observed in goods prices rather than services. This is because the production and transportation of goods are directly influenced by supply chain constraints and energy costs, whereas services tend to be more sensitive to labor market conditions and wage pressures. As a result, the initial impact of such global shocks typically manifests in goods inflation before potentially propagating over into services inflation over time.

Within this context, we observe a significant rise in goods inflation, particularly in the US, Euro area, and the UK. At the same time, the increase has been more moderate in Japan and Switzerland. This pattern contrasts sharply with pre-pandemic trends where goods inflation across countries was broadly similar. In this sense, it’s worth highlighting the dynamics in Japan where, as discussed in detail in our monthly Japan CPI reports, the yen's depreciation has significantly contributed to the elevated and persistent goods inflation. The weaker yen has increased import costs, directly impacting prices for imported goods, thus sustaining higher inflation levels in Japan compared to other regions. This contrasts with other countries where goods price deflation has contributed to a moderation in headline inflation.

The picture changes considerably when we turn to service inflation. We see a common upward shift in the level of service inflation across countries relative to the pre-pandemic pattern. However, unlike goods inflation, there has been no notable return to pre-pandemic levels, and inflation persistence remains high. The sustained increase in service inflation highlights that: while the shocks impacting goods prices may have moderated, the structural factors driving service inflation—for example labor costs and demand for services—continue to exert pressure, making it a key area of concern for policymakers.1 In particular, we have highlighted how monetary policy, through its effect on rental inflation, could potentially contribute to making this inflation relatively more persistent (we refer to this as the Catch-22 effect of monetary policy).

Monetary Policy Challenges

Before the pandemic, the BOE, BOJ, ECB, Fed, and SNB faced a common challenge: achieving their inflation targets from below. However, the current landscape reveals differing challenges across these central banks. In Japan and Switzerland, monetary policy responses have relied on the exchange rate. The strength of the Swiss franc has been a tool to curb goods inflation, while in Japan, the weaker yen has contributed to goods inflation, aimed at adjusting domestic inflation through wage growth, while fiscal measures have helped contain services inflation.

The differences in the behavior of various inflation aggregates across countries highlight the importance of country-specific factors in shaping inflation trends. For example, both the US and the UK are experiencing relatively high core and service inflation, but the underlying drivers may differ. In the US, fiscal policy and stronger aggregate demand are likely contributing to upward pressure on domestic inflation. This environment might necessitate a tighter monetary policy stance by the Federal Reserve, likely requiring it to maintain high rates (relative to pre-pandemic) to ensure that demand-side pressures do not entrench inflation expectations.

In contrast, the situation in the UK is more complex. Higher mortgage rates—driven by previous rate hikes—appear to be contributing to elevated service inflation, particularly through their impact on rental costs and housing-related services. To address this, a gradual easing of monetary policy could help alleviate the upward pressure on service inflation by reducing the cost of borrowing over time, and stabilizing consumer costs.

Similarly, the Euro area faces persistent core and service inflation, in a context in which growth slows in its major economies. This situation presents a dual challenge for the European Central Bank: the need to address inflation persistence while recognizing the broader economic slowdown. The ECB in the last policy meeting seemed to have chosen an approach in calibrating policy directed at avoiding a too-tight policy stance that could exacerbate economic deceleration in countries already facing downturns.

The differences across inflation measures that we have discussed above, also emphasize the role of structural and policy interdependencies. This interdependence suggests a growing need for monetary policy strategies that consider external developments. I would say that this is particularly true for all the aforementioned central banks, except the Federal Reserve.

For instance, financial market integration and the role of the yen carry trade, particularly in early August, highlighted the importance of a multilateral perspective on policy normalization in both the US and Japan. Following this period of volatility, communication coming from the Bank of Japan has stressed the importance of financial market stability as a prerequisite for any policy actions.

Similarly, from the SNB’s perspective, the economic ties between Switzerland and the Euro area present challenges. An accelerated pace of policy normalization by the ECB could pressure the Swiss franc to appreciate further, potentially requiring the SNB to resume more aggressive foreign exchange interventions to limit the Swiss franc’s appreciation.

Conclusions

In our inflation reports, we analyze inflation developments across various measures at the level of individual countries. However, in this blog, I have adopted a global perspective, highlighting differences in inflation dynamics across countries and comparing them to the pre-pandemic period. This initial analysis suggests that a 'one-size-fits-all' approach is no longer suitable for interpreting inflation trends or for designing monetary policy strategies going forward. The diverse inflationary pressures and responses observed across different regions indicate the need for country-specific monetary policy strategies that take into account the unique economic contexts of each country including the possible spillovers coming from external policy developments.

In the pre-pandemic context, low inflation and low interest rates were common features across advanced economies, leading to a flat and predictable monetary policy environment. However, our analysis suggests that we are far from returning to that scenario. Inflationary pressures are still present and materialize at different levels among countries. This shift might be a product of the structural changes occurring in these economies which have altered the landscape of monetary policy considerably.

Appendix

Table 1: Inflation targeting by country/region

Source: FED, BoE, ECB, SNB and BoJ.

Methodological Notes

In the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) calculates the R-HICP, which differs from the CPI in two major respects. First, the HICP includes the rural population in its scope. Second, and more importantly, the HICP excludes owner-occupied housing.

In Switzerland and the UK, however, the HICP methodology exactly matches that used for the Euro Area, which is calculated by the ECB. Note that, for the UK, the equivalent of the HICP is the CPI. The CPIH corresponds to the version that includes a measure of the costs associated with owning, maintaining, and living in one's own home, known as owner occupiers' housing costs (OOH).

Lastly, for Japan, there is no exact measure of the HICP calculated by the Bank of Japan. However, a measure of CPI excluding imputed rents is available, and this is what we compare to the HICP in other countries. The "imputed rents" measure represents "the rent a person would have to pay to own and occupy a property. Important to note, however, that Japan’s CPI includes all households with two or more persons, therefore excluding 1-person households, which corresponds to more than 25% of all households. In this sense, although the index excluding imputed rent also excludes 1-person households, it is more closely comparable to the HICP.

Here, it is important to note, though, that for all countries except the Euro area, this measure of service inflation includes owner-occupied rent along with rent inflation.

Sorry!!! It is Gianluca!!!! How silly of me 😀😀😀

Thank you Stefan, a great study that deserves a second, careful, read